IWA Policy on Freight on Inland Waterways

Previous version of policy dated April 2016

This version:

- Agreed by Inland Waterways Freight Group February 2024

- Approved by Trustees 21st February 2024

Summary of policy

- IWA supports the use and development of freight carriage on UK inland waterways, where this is sustainable in economic, environment and social terms.

- IWA promotes the benefits of modal shift of freight from road to water as a contribution to moving towards ‘net zero’ in terms of carbon emissions to the atmosphere.

- IWA will lobby waterway authorities to maintain waterways to statutory standards and in suitable condition for modern freight carrying vessels where freight use is a real possibility.

- IWA believes in multi-functional use of waterways by freight and leisure craft.

- IWA will press navigation authorities to market and facilitate opportunities for freight traffic on the inland waterways.

- IWA supports the continuing enhancement of waterway capacity and development of freight facilities to accommodate modern freight vessels on waterways with significant freight potential.

- IWA will lobby Government and planning authorities to consider waterway freight transport in drawing up development plans and identifying (and protecting where appropriate) locations for industry and freight interchanges.

- IWA supports the principle of safeguarding of wharves for freight where there are traffic prospects and the wharf is suitably located for modern cargo operations.

- IWA supports the continuation and expansion of Government funding, for example through grants, to encourage modal shift from road to water.

- IWA will seek to raise awareness of the opportunities for and advantages of waterborne freight transport on UK inland waterways, in co-operation with other like-minded lobby groups.

- IWA recognises the benefits of freight traffic on smaller waterways in encouraging retention of commercial vessels of heritage interest and in maintaining the channel cross-section

1. Introduction

1.1 This is a policy statement by the Inland Waterways Association (IWA) which sets out the position with regard to freight traffic on inland waterways in Great Britain. It covers all types of freight traffic on all inland waterways within the remit of the annually published UK Government statistics on waterborne freight on inland waterways [1].

1.2 It begins by introducing the topic, sets out the background to inland freight waterways in the UK and describes barriers to the development of waterborne freight. Section 4 then sets out IWA’s policies.

1.3 The Inland Waterways Association is a registered charity, founded in 1946, which advocates the conservation, use, maintenance and development of the inland waterways of the British Isles and promotes their fullest use for appropriate commercial and recreational purposes.

1.4 From its earliest days, IWA’s founders were concerned to maintain freight traffic on the waterway system, as well as encouraging leisure boating and other uses. Since then, conditions have changed and IWA recognises that many smaller waterways are no longer suitable for large-scale freight carriage, although they can often support small scale operations. However, many larger gauge waterways have continued to be used for freight transport and have adapted to modern methods of freight handling, although barriers remain to the realisation of their full potential. Currently (in 2011) over 1000km of waterways are in regular use in the UK for larger scale freight traffic.

[1] Waterborne Freight in the United Kingdom. Department for Transport. Published annually.

1.5 IWA set up the Inland Shipping Group in 1971 to investigate, promote and encourage the development of large-scale inland water transport in Britain as a contribution to the solution of transport, resources and environmental problems. The group operates today as a sub-committee of IWA’s Navigation Committee known as the Inland Waterways Freight Group. IWA publications on waterborne freight are detailed in Appendix A.

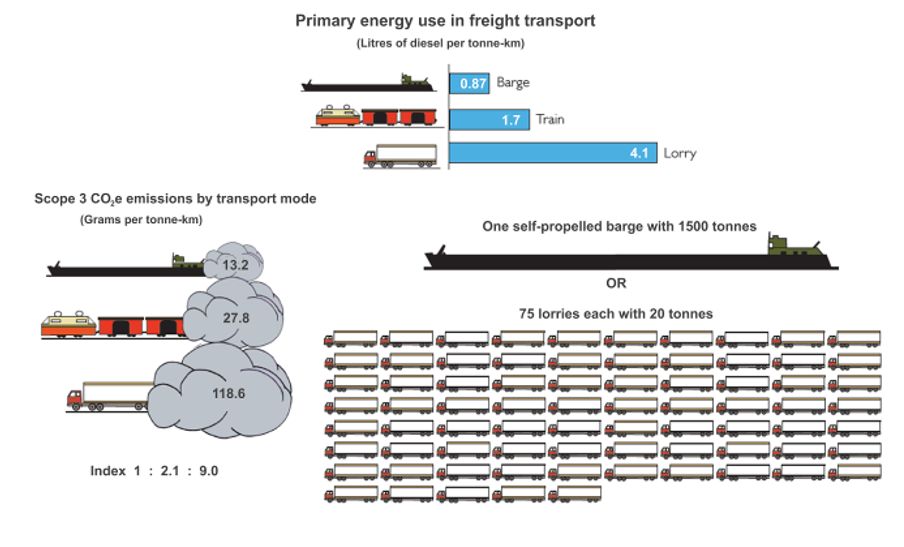

1.6. Use of waterway transport can have environmental benefits in terms of reducing fuel use per tonne kilometre and reducing traffic congestion and emissions associated with slow moving and stationary vehicles. Transporting the same tonnage of freight between two points by water instead of road has the potential to reduce by three quarters the amount of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emitted (see diagram below). Efficiency can be improved further where sustainable fuels are used and tides can be used beneficially to provide free, natural energy.

Notes:

- The emission figures above are in CO2e (scope 3) from the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero 2023 emission conversion factors: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2023

- There was no obvious emission factor for tugs, so ‘Cargo – general cargo – average’ was used. The emission factor for ‘Freight train’ was used and ‘HGV (Rigid >17t, 100% laden)’ was used for HGVs.

- The fuels consumed that make up the emission factors are based on the average for that sector in the UK. Given that commercial vessels are likely predominately to use low sulphur fuel oil and marine gas oil, then vessels solely using Hydro-treated Vegetable Oil (HVO) will have significantly lower emissions than is represented above. For example, the scope 1 emission factors for marine gas oil (MGO) are 2.77 kg CO2e compared to 0.03558 kg CO2e for HVO (i.e. using HVO in place of MGO as fuel for an inland waterways vessel achieves a reduction in scope 1 emissions of 98.72%).

- The tonnage of single consignments of cargo carried by inland barge in the UK is routinely up to 3500 tonnes, more than double the tonnage considered in this diagram, with commensurate emissions reductions.

2. The UK inland waterways and freight

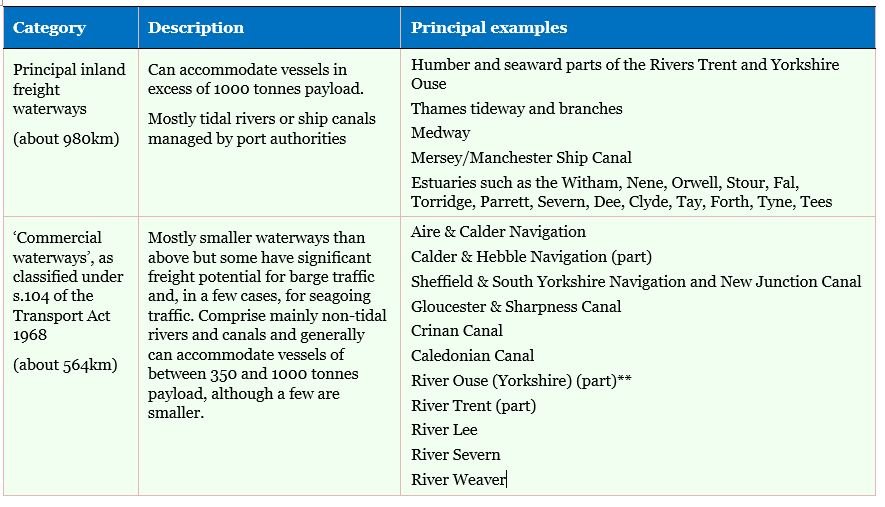

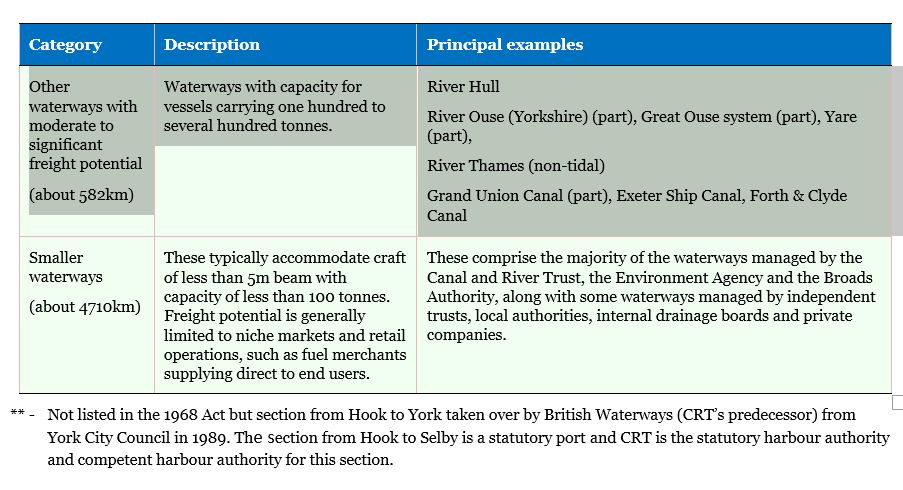

- principal inland freight waterways (most of which are managed by port authorities);

- freight waterways defined as ‘Commercial Waterways’ by the Transport Act 1968 (managed by The Canal and River Trust (CRT));

- other waterways with significant freight potential (managed by a variety of public bodies and port authorities);

- smaller waterways (managed by the CRT, the Environment Agency and the Broads Authority, as well as a variety of other public and private bodies).

Notes

[2] Figures as tonne-kilometres from Transport Statistics Great Britain 2020. Published annually by the Department for Transport (DfT).

[3] These waterways are managed by the Canal and River Trust and by Scottish Canals, who have a duty to make them principally available for the carriage of freight and to maintain them to allow passage of vessels of defined sizes.

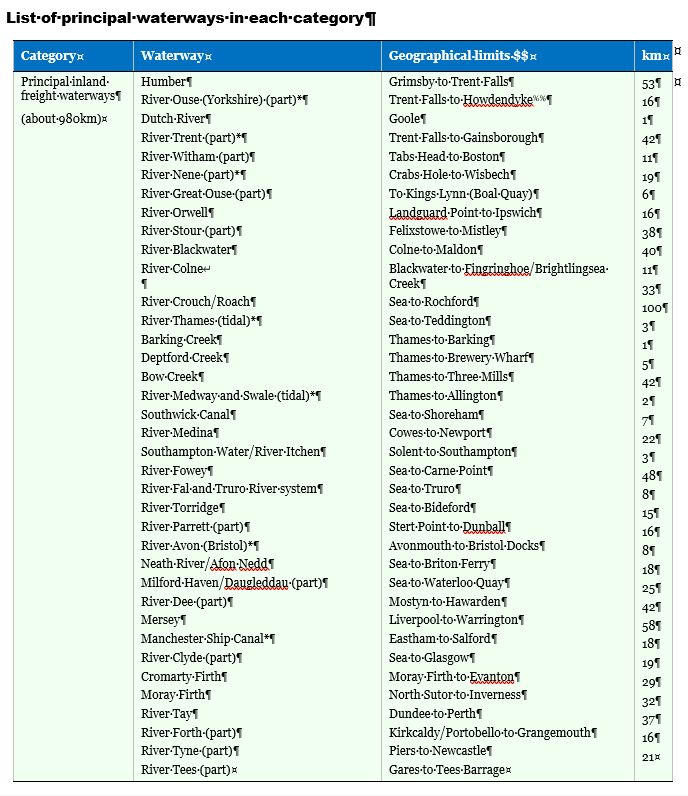

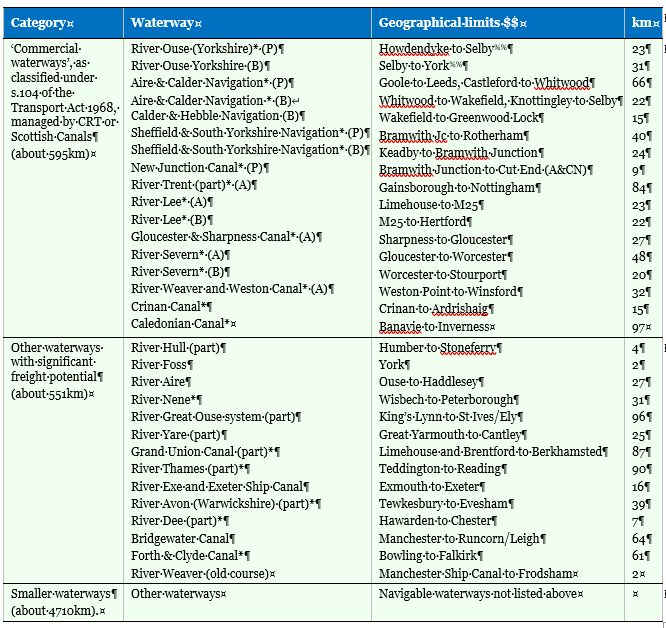

2.3. The characteristics of these categories and principal examples are set out in the table below.

2.4 Lists of currently navigable waterways falling within each category and lengths available for freight transport are given in Appendix B.

2.5 Additional freight potential would be created by investment in Commercial Waterways as classified under s.104 of the Transport Act 1968 to enable them to be navigated by larger vessels and by vessels carrying containers. Further potential may be provided by the re-opening in the future of waterways that are not navigable at present[1].

2.6 According to UK Government statistics, total traffic on the UK inland waterways network in 2009 amounted to 41.4 million tonnes lifted and total freight movement of 1.3 billion tonne-kilometres. Most of the traffic is on tidal inland waterways.

2.7 Traffic on the UK inland waterway system includes:

- internal traffic with its origin, route and destination entirely within inland and categorised waters[2], usually carried by vessels only suitable for operation on inland waterways;

- traffic entering inland waterways from sea in vessels from other UK ports and travelling inland;

- traffic entering inland waterways to or from foreign coastal or inland ports or offshore operations and travelling inland.

2.8 Many types of cargo can be carried on inland waterways but costs of cargo handling and changing onward mode of transport influence competitiveness. This can be offset by terminals, storage and distribution and manufacturing facilities being at waterside locations. Dry and liquid bulk cargoes are typically important as they can be loaded and discharged efficiently, although the increased use of containerisation means that, where waterways can accommodate vessels carrying containers, most types of goods can be carried competitively, including perishable goods requiring refrigeration.

2.9 With properly managed waterways, waterborne transport is as reliable as other modes and therefore suitable for the ‘just-in-time’ approach often adopted in modern supply chains.

2.10 UK Government policy on waterways is to encourage transfer of freight from road to water where this is practical, economically viable and environmentally desirable[3] and to encourage effective use of the planning process to achieve this[4]. Planning delays and planners’ failure to implement this policy are principal factors that inhibit the development of water freight and dealing with this must be a focus of efforts to develop and increase water freight in the UK. Government policy on ports[5] recognises that coastal shipping and inland waterways freight transport can be viable for certain flows to and from ports and states that use of inland waterways for the movement of goods to and from the port must be considered.

3. Barriers

3.1 IWA considers that there is untapped potential for transfer of freight to inland waterways but that this is constrained in the UK by a number of barriers, including:

- a lack of wharves at which cargo handling, storage and waterside manufacture/value added operations can take place;

- with regard to consenting planning applications involving inland waterways freight infrastructure and wharves, the inability of the UK’s planning system to operate within time frames that permit businesses to take advantage of water freight opportunities;

- lack of appropriate continuing development of waterway infrastructure, for example, raising bridge headrooms to facilitate use of container barges and increasing lock sizes to facilitate the use of larger, more cost-effective and environmentally friendly vessels;

- lack of operational experience in many types of industry, where transport managers are unfamiliar with processes, availability and costs, so rarely consider waterborne transport as an option;

- lack of knowledge about inland water-freight operational issues in some navigation authorities;

- inadequate promotion by Government and Government bodies of waterborne freight transport as a modern, environmentally desirable, transport mode;

- excessive costs associated with vessels using some infrastructure;

- a planning system that does not adequately take account of waterway freight transport infrastructure needs at national, regional or local levels;

- the lack of co-ordination between Government departments on waterborne freight transport matters, where the Department for Environment, Fisheries and Rural Affairs (Defra) is responsible for supporting waterways managed by the Canal and River Trust, the Environment Agency and the Broads Authority, the Department for Transport (DfT) is responsible for shipping and freight grants and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) is responsible for planning;

- some water freight infrastructure being in the hands of private companies with little or no interest in the development of inland waterways freight;

- commercial waterways operated by Canal and River Trust falling under the responsibility of an inappropriate Government department, namely Defra, when use of these waterways for freight transport should be the responsibility of the DfT.

3.2 Land availability and planning constraints continue to be a major constraint on development of inland waterway freight transport, especially in urban areas, where there is often pressure from planners and developers to use waterside sites for more lucrative housing developments and freight wharves are seen as bad-neighbour industries and a source of planning blight. Some wharves on the Thames have been safeguarded, such that there is a presumption for use for freight and this approach is being considered in other areas. Where this is done, safeguarding for port related activities or water freight activities must be clearly stated and such use must take priority over all other uses of safeguarded facilities. All safeguarded wharves and facilities must be afforded outline planning consent for use in connection with water freight activity.

3.3 IWA policies set out below aim to remove such barriers and encourage modal shift of freight from road to water.

4. IWA Statement of Policy

IWA’s overall policy regarding freight use of waterways

4.1 IWA supports the use and development of freight carriage on UK inland waterways, to deliver economic, environmental and social benefits, as part of an integrated freight transport system in the UK and as an integral part of the European maritime and inland waterway network.

4.2 IWA promotes the benefits of modal shift of freight from road to water as a contribution to moving towards ‘net zero’ in terms of carbon emissions to the atmosphere.

4.3 IWA will lobby waterway authorities to maintain waterways and other infrastructure in suitable condition for modern freight carrying vessels where freight use is a real possibility, as appropriate to their status (see below), and vigorously promote all such use.

4.4 IWA believes in multi-functional use of waterways and supports the principle that freight waterways should be available for use by leisure craft (and vice versa), subject to appropriate management where necessary to ensure that such uses are compatible with safety and port security considerations.

4.5 IWA will lobby Government and planning authorities actively to promote waterway freight transport when planning freight transport infrastructure and locations of industrial development and freight terminals.

4.6 IWA supports the continuation of Government grants to encourage modal shift from road to water[6] and believes that the Government department responsible for transport should also provide funding to assist Government supported navigation authorities to maintain and upgrade appropriate waterways for use by large, modern freight vessels.

4.7 IWA will press for grant support to take account of fuel use and zero emissions technology that deliver reductions in CO2 emissions, as well as congestion, where grant is based on road miles saved by transfer to water[7].

4.8 IWA will seek to raise awareness of the barriers to development of, opportunities for and advantages of waterborne freight transport on UK inland waterways, through lobbying, representation, waterway events and publications (see Appendix A for list of IWA freight publications) and will co-operate with other organisations involved in promoting freight use of waterways[8].

4.9 IWA will promote the safeguarding of wharves and water freight infrastructure and lobby for all such facilities to have automatic outline planning consent for waterway freight related activity.

Specific policies for the principal freight waterways

4.10 On the principal freight waterways, where the navigation authorities’ activities often relate mainly to seagoing traffic, IWA will press these authorities actively to market and facilitate opportunities for inland waterway carriage of freight, including publicising links to other inland waterways, where these are available.

4.11 IWA supports the continuing enhancement of waterway capacity and freight facilities to accommodate current and predicted developments in river-sea shipping practice.

4.12 Principal freight waterways, especially tidal waterways and those with tidal links, should be available 24 hours per day.

4.13 IWA supports the development and maintenance of inland terminals for freight, including containers, and will press Government, Government agencies, navigation authorities and planners actively to support and facilitate such developments.

Specific policies for commercial waterways designated under the Transport Act 1968

4.14 IWA will press for and support the Canal and River Trust and other owners and operators of commercial waterways designated under the 1968 Act, in partnership with others, in removing ‘pinch-points’ to achieve improvements in waterway capacity, where this will assist transfer of freight to water. In particular a programme of enlarging locks, deepening channels and increasing bridge headroom should be a target where opportunities arise to accommodate vessels carrying containers.

4.15 IWA supports the development and maintenance of inland terminals for freight, including containerised traffic.

4.16 IWA believes that the duties under the 1968 Act to make commercial waterways principally available for the carriage of freight and to accommodate freight vessels of specified dimensions should be retained and extended where there are existing freight operations which are economically, socially and environmentally sustainable or where there are prospects for such operations in the future.

4.17 IWA accepts that circumstances change over time and that changes in waterway classification may thus be appropriate from time to time.

4.18 IWA believes that a structured working group including water freight stakeholders should be set up to review the existing classification of commercial waterways, to advise CRT and other owners and operators of commercial waterways designated under the 1968 Act on this issue and to advise the Secretary of State on the issues and options when proposals are received to reclassify a commercial waterway.

4.19 However, where the downgrading of a waterway from a ‘commercial waterway’ to a ‘cruising waterway’ under s.105 of the 1968 Act is proposed, IWA believes the following steps are necessary and may object to the proposed Order unless:

- a full appraisal has been undertaken of current traffic and future traffic prospects, in the light of any Government financial incentives for freight to move from road to water to secure climate change or other environmental benefits;

- options for improving efficiency of the waterway operation and reducing costs, for example by modernisation of locks and centralised or automatic operation, have been fully considered and documented;

- these considerations have been fully documented in the form of a benefit : cost analysis and made available to consultees;

- operators have been fully consulted;

- it appears to the IWA that these aspects are being taken into account by the Secretary of State;

- in the opinion of the IWA, there are no longer any prospects of significant use of the waterway for freight traffic.

4.20 Where additional funding is required to maintain such waterways for freight traffic, this should be assisted by funding from the Government department responsible for transport.

4.21 IWA accepts that it may not always be practicable to maintain statutorily required depths on a commercial waterway that is not for the time being regularly navigated by deep-draughted vessels. In line with the Ombudsman’s report regarding a complaint from a carrier[9], waterways should be maintained so that they can be put in order promptly when required for freight traffic and always within one month of such a justified complaint being made in writing. Such rectification work must be carried out without adversely affecting existing water freight operations.

4.22 Tidal commercial waterways and those with tidal links should be available 24 hours per day. Other freight waterways should be available 24 hours per day where traffic warrants it.

Specific policies for other waterways with significant freight potential

4.23 IWA will support navigation authorities and other stakeholders in seeking opportunities for freight traffic.

4.24 IWA will support navigation authorities and partners in improving waterway capacity for freight, where there are realistic prospects of attracting freight traffic.

Specific policies for smaller waterways

4.25 Many smaller waterways can support freight transport, including retail activities, in certain circumstances and IWA encourages such uses where these are sustainable.

4.26 As well as benefits in environmentally friendly transport, IWA recognises the benefits of freight traffic in encouraging retention of commercial vessels of heritage interest and the role of deeper draughted vessels in maintaining channel depth and identifying pinch points.

4.27 IWA will press navigation authorities when dredging to dredge to the full constructed channel profile and to remove pinch points where the original gauge has been compromised.

IWA Policies applying to all freight waterways

4.28 In support of the freight use of inland waterways, IWA will press navigation authorities on waterways with freight traffic or freight potential to:

- ensure provision of efficient operational track and, if underused for a period, ensure equipment is regularly exercised to maintain operability (for example to prevent accumulation of silt and rubbish behind lock gates);

- publish widely the maximum vessel size accepted for each waterway, review regularly published data for accuracy and ensure that the waterway remains unobstructed for such vessels;

- ensure that the waterway gauge does not become degraded, to remove pinch points that have arisen and to increase clearances where opportunities arise;

- actively promote and support the use of their waterways for freight transport, in support of Government policy;

- recognise that waterway carriers and shipping agents, should be regarded as primary customers of the freight waterway track provider, as well as the owner of the goods;

- adopt a proactive, “can-do” approach and show a willingness to discuss traffic opportunities without preconceptions;

- be willing to deal with the whole range of sizes and types of responsible operator;

- provide a customer service contact regarding freight matters for freight users.

4.29 In support of the freight use of inland waterways, IWA will press navigation authorities on waterways with freight traffic to:

- provide facilities at suitable locations for water supply and for disposal of sewage, garbage and oily waste that are accessible to freight vessels;

- provide segregated layby facilities, suitable for use by freight vessels, at critical points such as at lock approaches, at overnight mooring locations or where needed on tidal waterways for vessels awaiting the tide;

- provide water level and air draught gauges at appropriate locations;

- provide adequate publicity of operating arrangements for both freight and leisure vessels;

- inform freight vessel operators of and be transparent about any problems that may restrict availability of the waterway for freight use;

- consult freight vessel operators regarding planned maintenance and refurbishment/ improvements to ensure appropriate provision for and minimum disruption of freight traffic during the works and take all possible precautions not to compromise freight traffic when undertaking such works;

- ensure that internal communication within the organisation is established so that the needs of both freight and leisure users are considered together.

4.30 IWA will generally oppose any development which might serve to render ineffective, compromise, remove or decommission any wharf, wharfage site or freight infrastructure or restrict navigation by freight vessels, such as inappropriately located leisure or residential moorings, business barges or developments which restrict approaches to locks or bridges.

4.31 IWA will press Government, government agencies and planning bodies to:

- ensure retention of sufficient waterside land, with good land-based access, for provision of wharves, cargo handling facilities, waterside storage, distribution and manufacturing facilities and sites, in order to allow full development of the freight potential of the waterways;

- take account of the freight potential of waterways in drawing up national policy statements and local development documents, in relation to allocation of waterside land for industry and for multi-modal freight facilities;

- establish mechanisms for co-operation between Government departments on waterway freight issues.

4.33 IWA supports the principle of safeguarding of wharves for freight where there are traffic prospects and the wharf is suitably located for modern cargo operations. In cases where the only facility in a locality suitable for freight vessel operations is located in an area where such use is no longer appropriate in planning terms and there is existing or potential future demand for such a facility, IWA will not object to its loss provided that an alternative freight wharf is provided in a more suitable location before the existing facility is taken out of commission or otherwise rendered unusable.

4.34 IWA encourages review of the current waterborne freight grant regime from time to time by Government in light of developing initiatives to combat climate change.

4.35 IWA will assist in proving information and advice on safe navigation to leisure boaters using inland waterways also used by large freight vessels.

5. IWA Inland Waterways Freight Group

5.1 IWA will maintain an Inland Waterways Freight Group to:

- advocate the fullest use of categorised water and inland waterways in the British Isles for freight transport;

- promote research into and support for freight transport on categorised waters and inland waterways in the British Isles;

- liaise with the Department for Transport, navigation authorities, planning authorities, and other organisations whose activities are relevant to the role and development of inland shipping in the British Isles;

- publish information and promote communications in support of freight transport on waterways in the British Isles.

Notes

[1] An example of a recently restored waterway where freight potential has been identified is the Forth and Clyde Canal.

[2] Maritime and Coastguard Agency (2017) Categorisation of waters. Merchant Shipping Notice MSN 1837 (M) Amendment 2.

[3] Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2000) Waterways for Tomorrow.

[4] Association of Inland Navigation Authorities (2005) Planning For Freight on Inland Waterways. Report commissioned by the Association of Inland Navigation Authorities for DfT and Defra.

[5] Department for Transport (2012) National Policy Statement for Ports

[6] The modal shift revenue support (MSRS) grant scheme (as at 2023)

[7] Currently the calculation of the reduction in road mileage used in determination of amount of MSRS grant available for freight transferred to water does not take account of most motorway mileage.

[8] Such organisations will include, for example, Logistics UK (formerly the Freight Transport Association), CBOA (the Commercial Boat Operators’ Association), PIANC (the World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure) and ERSTU (the European River-Sea Transport Union).

[9] The Waterways Ombudsman (2007) Summary of Case No 181 – reluctance to give freight operator commitment to comply with statutory maintenance obligations. Report of the Waterways Ombudsman concerning complaint no. 181.

Appendix A

IWA publications on waterway freight

IWA (1965) New Waterways. Interim report of a development committee appointed by the Council of the Inland Waterways Association Ltd. 31pp.

IWA (1974) Barges or Juggernauts. A national commercial waterways development projection by the Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 40pp.

IWA (1975) Report on Continental Waterways. A contemporary study. A report of the Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 77pp.

IWA (1980) Waterways survival. A report on the condition and status of Britain’s waterways, past, present – and future. Inland Waterways Association. 27pp

IWA (1980) British Freight Waterways Today and Tomorrow. Ed. Mark Baldwin, Vice Chairman of the Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 64pp.

IWA (1990) The Inland Shipping Group – its role and policies. Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 24pp.

IWA (1996) UK freight waterways – a blueprint for the future. Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 11pp

Montgomery Watson Harza (2002) East Midands Waterway. Pre-feasibility report for the Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 12pp. plus maps.

Dyer E. (2002) River Severn Waste Study: a report of the volumes of waste produced in the areas along the River Severn Corridor. Report for the Inland Shipping Group of the Inland Waterways Association. 36pp.

IWA (2007) Waterways Freight. Inland Waterways Freight Group – Campaigning for greater use of inland waterways for freight transport. Information leaflet produced by the Inland Waterways Association. 4pp

IWA (2010) Waterways Freight. Inland Waterways Freight Group – Raising awareness of the opportunities of inland waterways for freight transport – the environmentally friendly way. Information leaflet produced by the Inland Waterways Association. 4pp

IWA Regular news features on inland waterways freight in Waterways, the magazine of the Inland Waterways Association.

Other relevant publications on waterway freight in the UK

DETR (2000) Waterways for Tomorrow. Department for Environment, Transport and the Regions.

Defra and DfT (2002) The Government’s response to the report of the Freight Study Group Freight on Water – A New Perspective. Report for Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and Department for Transport (DfT). Product code PB 7196. June 2002

Freight Study Group (2002) Freight on Water – A New Perspective. Report of the Freight Study Group chaired by Hugh Wenban-Smith for Report for Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions (DTLR). June 2002

AINA (2004) Planning for Freight on Inland Waterways. Report commissioned by the Association of Inland Navigation Authorities (AINA) on behalf of the Department for Transport and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. MDS Transmodal and Atkins prepared the Guide on AINA’s behalf.

Sea and Water (2005) The water freight review. 114pp.

London Thames Gateway Development Corporation (2006) Safeguarded Wharves Development Options Assessment. Final report. Report for LTGDC by URS Corporation, with: Baxter Eadie Ltd, Baker Rose Consulting LLP and Glenny Surveyors. Project No: 44407027.

Sea and Water (2006) The case for water. Why transporting freight by water is good for the environment and good for the economy. 36pp.

IWAC (2007) The Inland Waterways of England and Wales in 2007. What has been achieved since the publication of Waterways for Tomorrow in June 2000 and what needs to be done. A report by the Inland Waterways Advisory Council (IWAC).

Transport for London (2007) London Freight Plan – sustainable freight distribution: a plan for London. 108pp.

Peter Brett Associates (2008) River Trent Water Freight Feasibility Study – Current and Future Prospects. Project Ref: 20877/001. Doc Ref: Final Report. November 2008. Report prepared for British Waterways by Peter Brett Associates LLP.

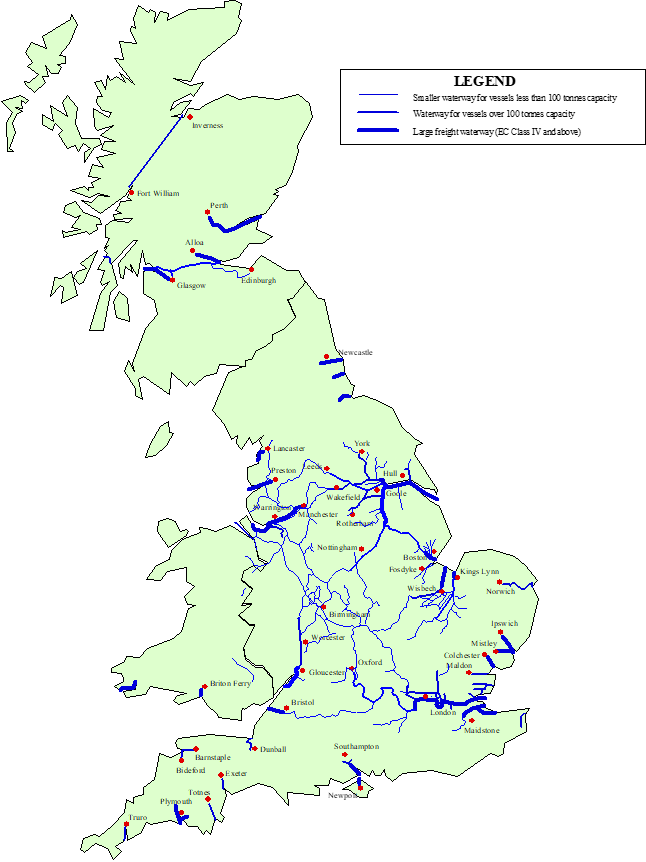

Capita Symonds (2008) Map of key inland waterways of Great Britain with freight potential. Report prepared by Capita Symonds for Department for Transport (DfT).

TCPA (2009) Policy advice note: Inland Waterways. Unlocking the Potential and Securing the Future of Inland Waterways through the Planning System. Produced by the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), with the support of British Waterways. June 2009

Canal & River Trust Freight Advisory Group (2014) A proposed policy for waterborne freight. Report of the Freight Advisory Group, Chair David Quarmby CBE, February 2014. 26pp.

Wiegmans, Bart (2018) The UK domestic water transport system: an evidence review. Report for the Government Office for Science Foresight programme by Dr Bart Weighmans, Delft University of Technology.

Highways England (2019) Water preferred policy. Guidelines for the movement of abnormal indivisible loads. 28pp.

National Infrastructure Commission (2019) Future f freight demand: Evidence base. Final report. Report for National Infrastructure Commission by MDS Transmodal. Ref: 218038R Final Reportv4. 189pp.

GPS Marine (2020) GPS Marine Tugs and Barges – River Transport for the Thames and Medway Estuaries. Case Studies of Three Major London Infrastructure Projects. January 2020. 24pp.

Appendix B – UK Freight Waterways

* – Included in DfT list of Key or Core Waterways with freight potential[1] (note this classification did not include many of the estuarial waterways, which are among the most important freight waterways)

(P) – Defined by CRT as a as a Priority Freight Route

(A) – Defined by CRT as a as a Category A Commercial Waterway

(B) – Defined by CRT as a as a Category B Commercial Waterway

$$ – Seaward limits for inland waterways are defined in terms of reasonable operating limits for inland barges and are generally the boundary between Class D waters and the sea[2]. Where summer and winter limits are different, the more appropriate has been chosen in the light of local conditions and current barge operations (if present).

%% – Not listed in the 1968 Act but taken over by British Waterways from York City Council in 1989 and subsequently by CRT. The section from Hook to Selby is a statutory port.

[1] Department for Transport (2008) Map of key inland waterways of Great Britain with freight potential. Report prepared by Capita Symonds for DfT.

[2] Maritime and Coastguard Agency (2017) Categorisation of waters. Merchant Shipping Notice MSN 1837 (M) Amendment 2.